The tragic sinking of the RMS Titanic in 1912 has woven itself into the fabric of storytelling and cultural expressions since its fateful voyage. From films to music, literature to folklore, the Titanic’s legacy remains a source of fascination, memorialization, and artistic inspiration.

Verses of Sorrow and Reflection

The sinking of the RMS Titanic in 1912 inspired a lot of poetic expressions capturing the huge loss. Poets, both renowned and emerging, turned to elegiac verse, filling newspapers and personal collections with varied emotional and artistic reflections.

Charles Hanson Towne’s “The Harvest of the Sea” praised the sacrifice of those lost, envisioning their spirits transcending the ocean’s depths.

Established poets like Thomas Hardy and Harriet Monroe contributed contrasting pieces: Hardy’s “The Convergence of the Twain” depicted the ship’s grandeur against nature’s indifference, while Monroe’s work adopted a more traditional, patriotic tone.

In later years, poets like E. J. Pratt and Hans Magnus Enzensberger continued to grapple with the Titanic’s legacy. Pratt’s “The Titanic” held financiers accountable for the disaster, emphasizing the iceberg as fate’s master. Enzensberger’s post-modernist approach in “The Sinking of the Titanic” critically questioned the event’s myth-building and cultural industry.

Songs Born of Tragedy

The sinking of the RMS Titanic in 1912 led to a profound musical response, sparking a surge of songs that resonated across various genres and cultures, reflecting the widespread impact of the disaster.

The immediate aftermath witnessed an outpouring of over a hundred songs in the United States alone, becoming what D.K. Wilgus described as possibly the largest number of songs inspired by any single event in American history. These songs, produced within days of the disaster, captured societal themes of the time, drawing lessons on wealth, social divisions, heroism, and moral judgment.

Themes of social disparity and the loss of difference between the rich and commoners in the face of tragedy were present in these songs. Speaking about the bravery of those who perished, many celebrated the heroic acts of prominent figures like John Jacob Astor, highlighting their sacrifice and high social standing.

The tragedy was not confined to a single genre. In the Southern United States, blues, bluegrass, and country singers found inspiration in the Titanic disaster. Bluesman Ernest Stoneman’s “The Titanic” became a massive hit, adapting lyrics from a poem seen in a newspaper. At the same time, other artists like Rabbit Brown, Frank Hutchison, and Blind Willie Johnson interpreted the sinking with an explicit religious message.

The event also found resonance across the Atlantic. British songwriters produced pieces invoking religious, chauvinistic, and heroic sentiments, commemorating the brave crew and survivors while encouraging contributions to assist those left behind. Polish rock band Lady Pank’s song “Zostawcie titanica (Leave the Titanic alone)” in 1988 added another layer to the variety of Titanic-inspired music.

In African-American culture, the sinking was seen as retribution for white racism. Lead Belly’s 1948 song “The Titanic” portrayed the ship as a symbol of white hubris and portrayed the rejection of black boxer Jack Johnson from boarding. Additionally, in black folklore, the story merged with the character “Shine,” a trickster figure aboard the ship. The Toast narrative depicted Shine’s refusal to save drowning white people, rejecting offers of wealth and women as retribution for their mistreatment of his people.

The variety and depth of musical expressions arising from the Titanic disaster emphasized its impact on diverse cultures and artistic interpretations, reflecting broader social narratives and perspectives on human tragedy, social hierarchy, and retribution.

The Titanic’s legacy continues to echo through the melodies and lyrics, immortalizing the event within the fabric of our collective cultural memory.

Cinematic Impact

At the forefront of popular culture’s engagement with the Titanic is James Cameron’s blockbuster film released in 1997. Within nine weeks of its debut, it became the highest-grossing film globally, reaching the historic milestone of being the first movie to amass $1 billion worldwide. By March 1998, the film had garnered over $1.2 billion, a record that stood until Cameron’s next project, “Avatar,” surpassed it in 2009. This epic drama centers on the romantic relationship between First Class passenger Rose DeWitt Bukater, played by Kate Winslet, and Third Class passenger Jack Dawson, portrayed by Leonardo DiCaprio.

James Cameron orchestrated the characters of Rose and Jack as an “emotional lightning rod for the audience,” a design to provide immediacy and emotional connectivity to the tragedy of the disaster. The intertwining love story is meant to humanize the disaster, offering the audience an emotional entry point into the tragedy.

With a staggering budget of $200 million, the film was the most expensive ever produced at the time. Extensive portions of the film were shot on a massive, nearly complete replica of the Titanic’s starboard side in Baja California, Mexico, ensuring a vivid recreation of the ill-fated ship. In 2012, marking the Titanic disaster’s centenary, the film was converted into 3D and re-released, coinciding with the tragic event’s hundredth anniversary. Notably, Cameron’s film is unique in being partially filmed aboard the vessel itself, resulting from the Canadian director’s visit to the Titanic wreck in two Russian submersibles during the summer of 1995.

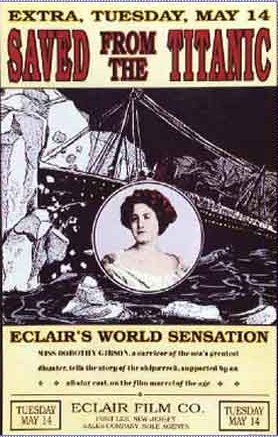

Early Depictions (1912–1943):

The first drama film, “Saved from the Titanic,” emerged only 29 days after the disaster. Star Dorothy Gibson, an actual survivor, presented a fictionalized account of her experiences. However, this film is now lost due to a fire destroying known copies.

Competing against this was the German film “In Nacht und Eis (In Night and Ice),” reenacting the collision and the panic on board but not depicting the evacuation. A Danish film, “Et Drama på Havet (A Drama at Sea),” and its follow-up “Atlantis,” depicted ship disasters, filmed on real liners, the latter, notably on the SS C.F. Tietgen. However, the Tietgen later sank for real when torpedoed by a German U-boat.

Later attempts and suggestions for a film emerged but were abandoned or faced challenges. The Nazi propaganda film “Titanic” (1943) showcased a fictitious conflict between figures like John Jacob Astor and Ismay, and its director faced severe consequences.

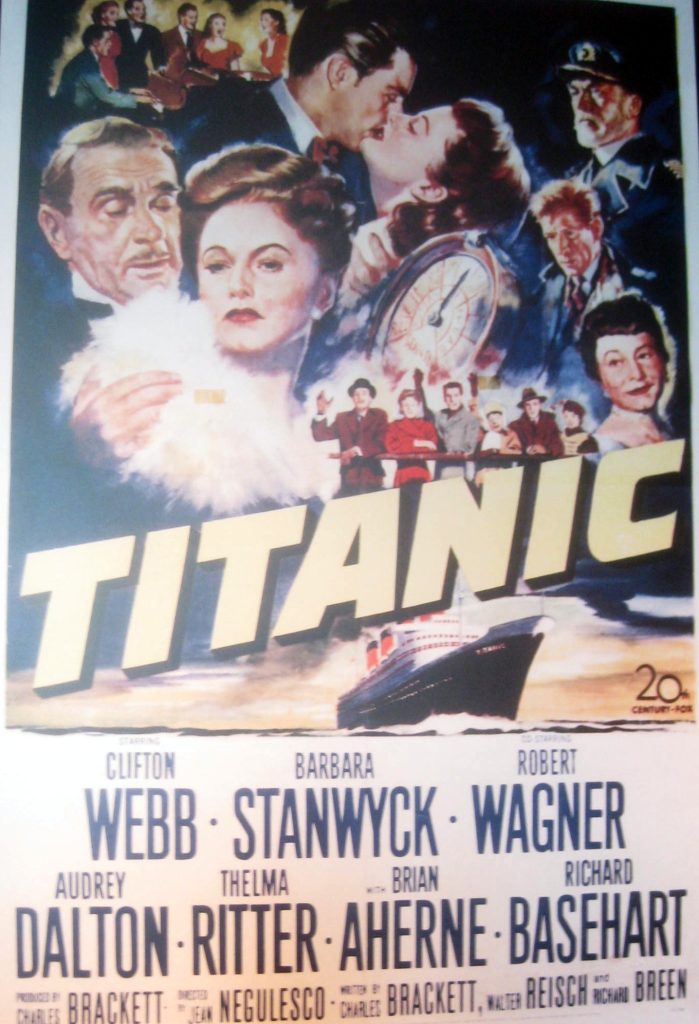

1953 – 2012:

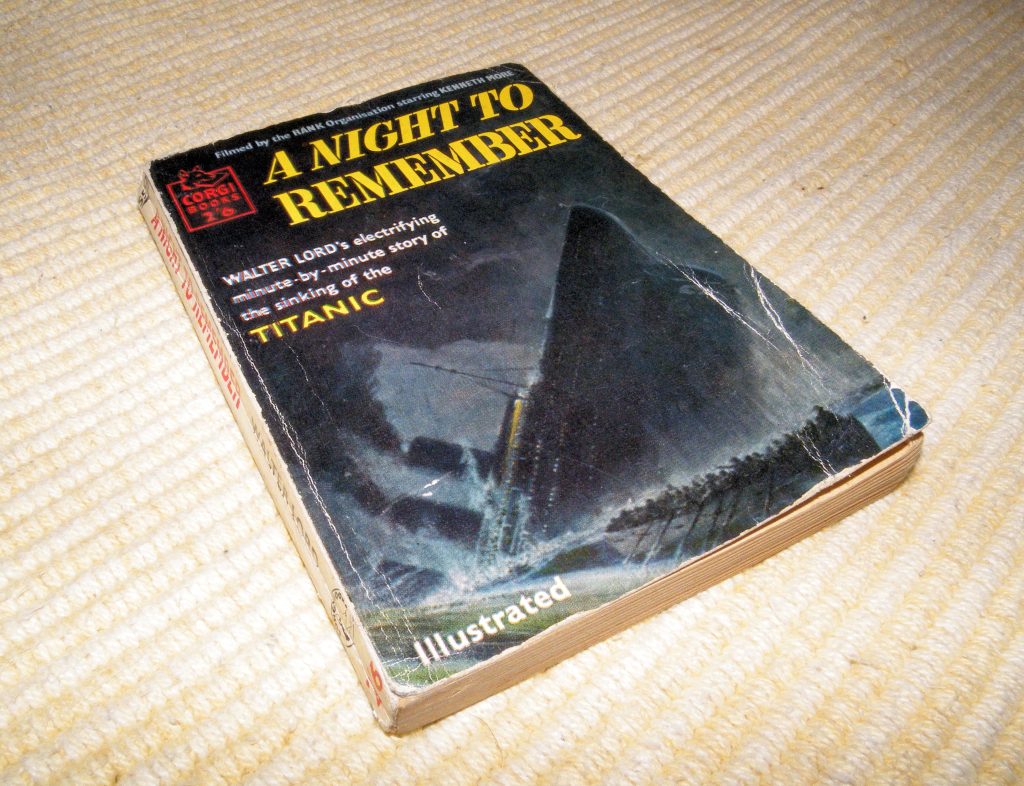

The film “Titanic” (1953) focused more on human drama than historical accuracy. Another film, “A Night to Remember” (1958), produced by William MacQuitty, detailed the sinking in a documentary-style manner. It was considered a modest success but has retained its artistic merit, becoming the prototype for disaster films.

“S.O.S. Titanic” (1979) displayed personal stories, portraying some figures in different lights, like Ismay as a villain. “Raise the Titanic” (1980) depicted a mission to salvage the ship for Cold War reasons but became a massive financial disappointment.

The Titanic also made a supernatural appearance in “Ghostbusters II” (1989), reimagining the ship as a ghostly vessel arriving in New York Harbor.

The sinking of the Titanic has also found resonance in the world of music. The Broadway musical “Titanic,” penned by Peter Stone and Maury Yeston, captured the drama of the ship’s journey and met both critical and commercial success. Its renditions of the human stories aboard the ship made the tragedy palpable to audiences. Additionally, Gavin Bryars’ musical composition “The Sinking of the Titanic” took a unique approach, portraying the haunting retelling of the orchestra that played as the ship met its demise.

Literary and Cinematic Contributions:

Walter Lord’s nonfiction book “A Night to Remember” and its subsequent cinematic adaptation in 1958 provided a comprehensive and compelling narrative of the disaster, marking an important contribution to the historical account of the Titanic’s sinking. These works are often regarded as essential resources for understanding the intricacies of the tragedy.

Folklore and Cultural Interpretations:

The Titanic’s legacy has even been interwoven with folklore and cultural narratives, one notable instance being the fusion of the Titanic story with the African-American folklore figure Shine. The tale, often conveyed in spoken-word performances or ‘toasts,’ uses the Titanic as a metaphor for the dangers of arrogance and exploitation, cautioning against blind trust in authority and systemic inequalities.

The lasting effect of the Titanic on popular culture is evidence of the human need to understand, commemorate, and explore historical tragedies through various creative mediums. Whether through films that capture the emotional gravity, musical compositions that bring out the auditory landscape of the disaster, or literary works that document its historical significance, the story of the Titanic continues to captivate and compel audiences worldwide, ensuring its place in the records of cultural history.